Low Monocytes Levels May Predict Remission, Slowed Disease Progression

Written by |

Cells of the innate immune system called monocytes can be useful biomarkers to predict the outcomes of people with sarcoidosis, a recent study has found.

The findings showed that patients with low levels of blood monocytes at diagnosis were more likely to achieve remission after two years and had less disease progression.

The study, “Monocytes in sarcoidosis are potent TNF producers and predict disease outcome,” was published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Sarcoidosis results from an overactive immune response that triggers clumps of inflammatory cells called granulomas to take root in various tissues.

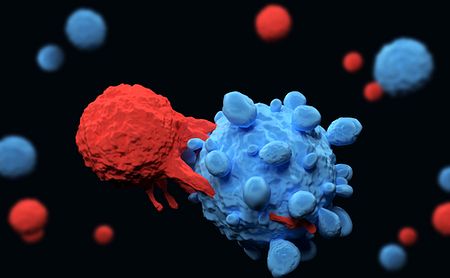

While T-cells — a type of immune cell — are thought to drive this process, the contributions of other immune cells, such as mononuclear phagocytes (MNPs), are less well-known.

MNPs comprise a class of cells that include alveolar macrophages (AMs), monocytes and monocyte-derived cells, and dendritic cells (DCs). All of these produce the pro-inflammatory molecule tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a key player implicated in sarcoidosis development.

Although AMs have been studied in sarcoidosis, dendritic cells and monocytes — which have been linked to sarcoidosis-related inflammation — have received less attention.

Now, researchers from Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet compared MNP populations in the blood and airway fluid of 108 individuals with sarcoidosis and 30 healthy people (controls). Their aim was to correlate their findings to two-year disease outcomes.

Of the participants with sarcoidosis, 20 were diagnosed with Löfgren’s syndrome, a milder form of the disease characterized by an acute onset and generally good prognosis.

Both Löfgren’s and chronic (non-Löfgren’s) sarcoidosis participants had elevated levels of monocytes in their blood as compared with the healthy controls. In particular, the sarcoidosis patients had higher levels of so-called intermediate monocytes in their blood. The airway fluid of non-Löfgren’s patients also had more of these cells than that of the controls.

More TNF-producing monocytes also were found in the airway fluid of non-Löfgren’s participants — but not Löfgren’s patients — at the time of diagnosis and throughout disease development. While dendritic cells also produced TNF, they did so less compared with monocytes.

The monocytes isolated from Löfgren’s and non-Löfgren’s patients showed different gene activity patterns, with those from non-LS individuals showing more active inflammation signaling pathways, such as that related to TNF.

“While AMs are numerous in [airway] fluid and undoubtedly play an important role in sarcoidosis, analysis of bulk [airway] cells may mask the contribution of less frequent monocytes/monocyte-derived cells and DCs,” the researchers wrote.

After two years of follow-up, 69 patients remained alive, including 18 in remission and 51 who developed chronic sarcoidosis. Among those now diagnosed with chronic disease, 32 were in stable condition and 19 developed progressive sarcoidosis.

Notably, patients who had high levels of blood intermediate monocytes at their time of diagnosis were less likely to achieve remission after two years. The levels of monocytes producing TNF at the time of diagnosis also were associated with progressive disease, suggesting that TNF-producing intermediate monocytes are linked to worse outcomes.

“Collectively, our data reveal an important role for monocytes/monocyte-derived cells in sarcoidosis,” the investigators concluded, while calling for further research.

“Continued in-depth analysis of MNPs may help to better understand the clinical heterogeneity and may pave the way to identify biomarkers and treatment options to help sarcoidosis patients clear the disease,” they wrote.